7 Quadratic curves

Algebra gives us a pretty good way of understand linear functions and intersections of their graphs. However, we are going to want more than this. In particular, we will want to understand how to analyse stationary points on surfaces \(z=f(x,y)\). Is there some sort of analogous statement to that which says that a stationary point on \(y=f(x)\) is a maximum when \(f''(x)<0\)? This will need some understanding of quadratic functions, and conic sections in particular.

7.1 Circles

7.1.1 The equation of a circle

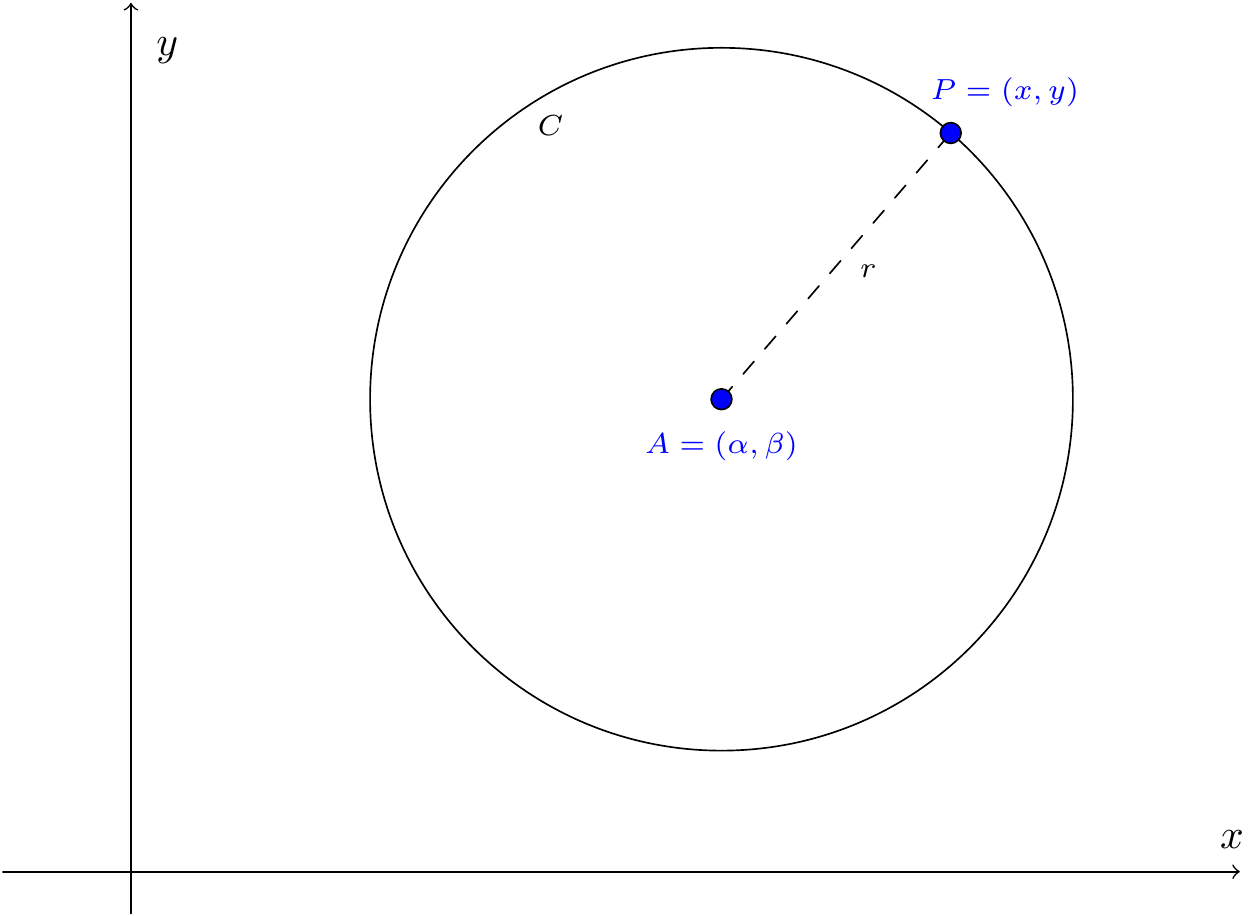

Let \(C\) denote the circle with centre \(A(\alpha,\beta)\) and radius \(r\). Thus \(C\) consists of all those points whose distance from \(A\) is \(r\).

Figure 7.1: A circle

We know that \(|AP|^2=(x-\alpha)^2 +(y-\beta)^2\), so the equation of the circle is \[(x-\alpha)^2 +(y-\beta)^2=r^2.\]

7.1.2 Intersection of a line and a circle

Before doing this algebraically, think geometrically what might happen:

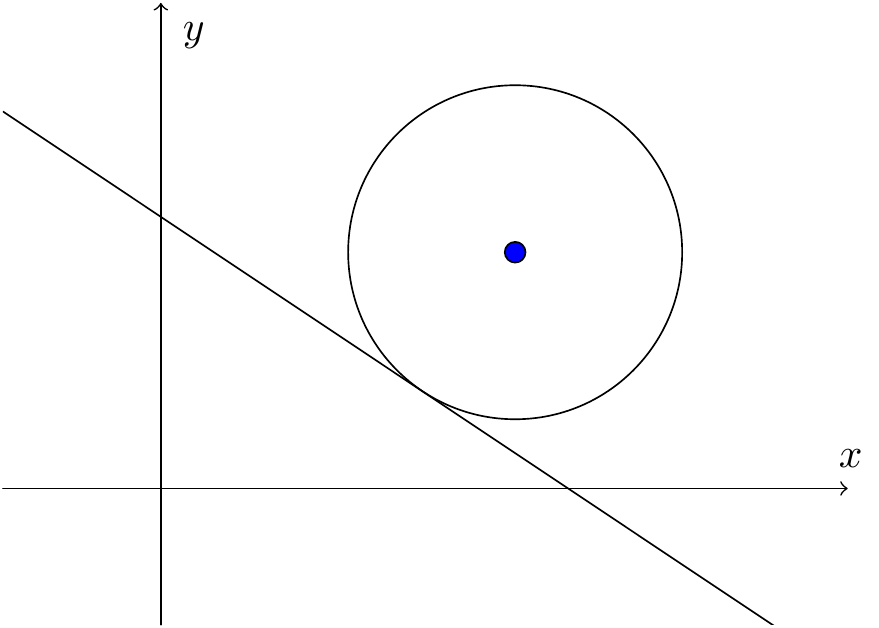

the line might miss the circle completely, so that there are no points on intersection;

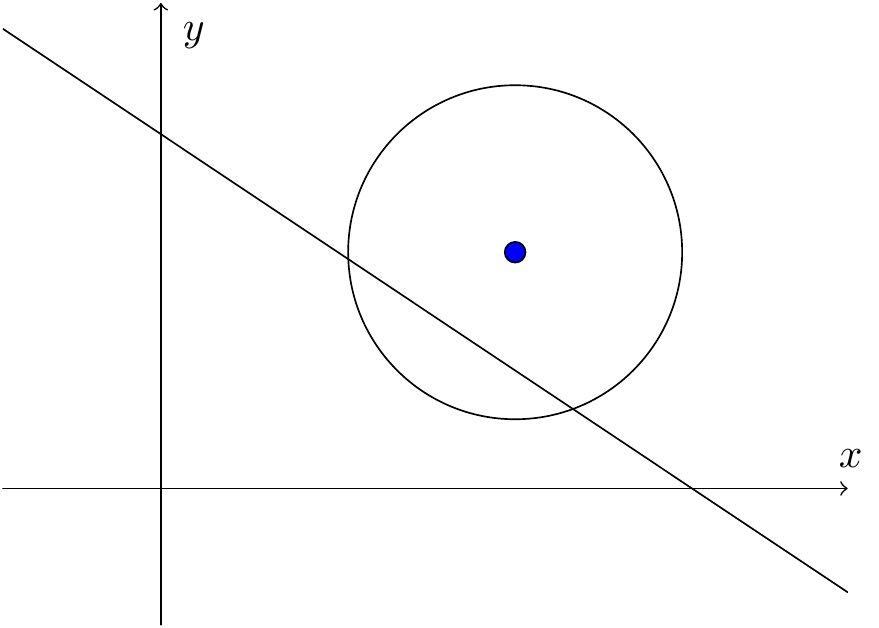

the line might touch the circle as a tangent, so that there is one point of intersection (and you should get the idea that as it is a tangent, there is a sense in which this point is a double point of intersection);

the line might cut the circle, and meet it at two distinct points.

Figure 7.2: A line missing the circle

Figure 7.3: A line tangent to the circle

Figure 7.4: A line cutting the circle twice

Let’s check this algebraically.

Let the line \(\ell\) be \(ax+by=d\). We need to solve \[\begin{aligned} (x-\alpha)^2+(y-\beta)^2&=r^2 \\ ax+by&=d\end{aligned}\] If \(b\ne0\), then \(y=\frac{1}{b}(d-ax)\) and \[(x-\alpha)^2+\left(\frac{1}{b}(d-ax)-\beta\right)^2=r^2\] This is a quadratic in \(x\) and there are three possibilities, corresponding to the geometrical situation above:

the quadratic does not have any real roots;

the quadratic has a single, repeated real root;

the quadratic has two distinct real roots.

Example 7.2 Let \(C\) be the circle with the centre \((2,3)\) and radius 5.

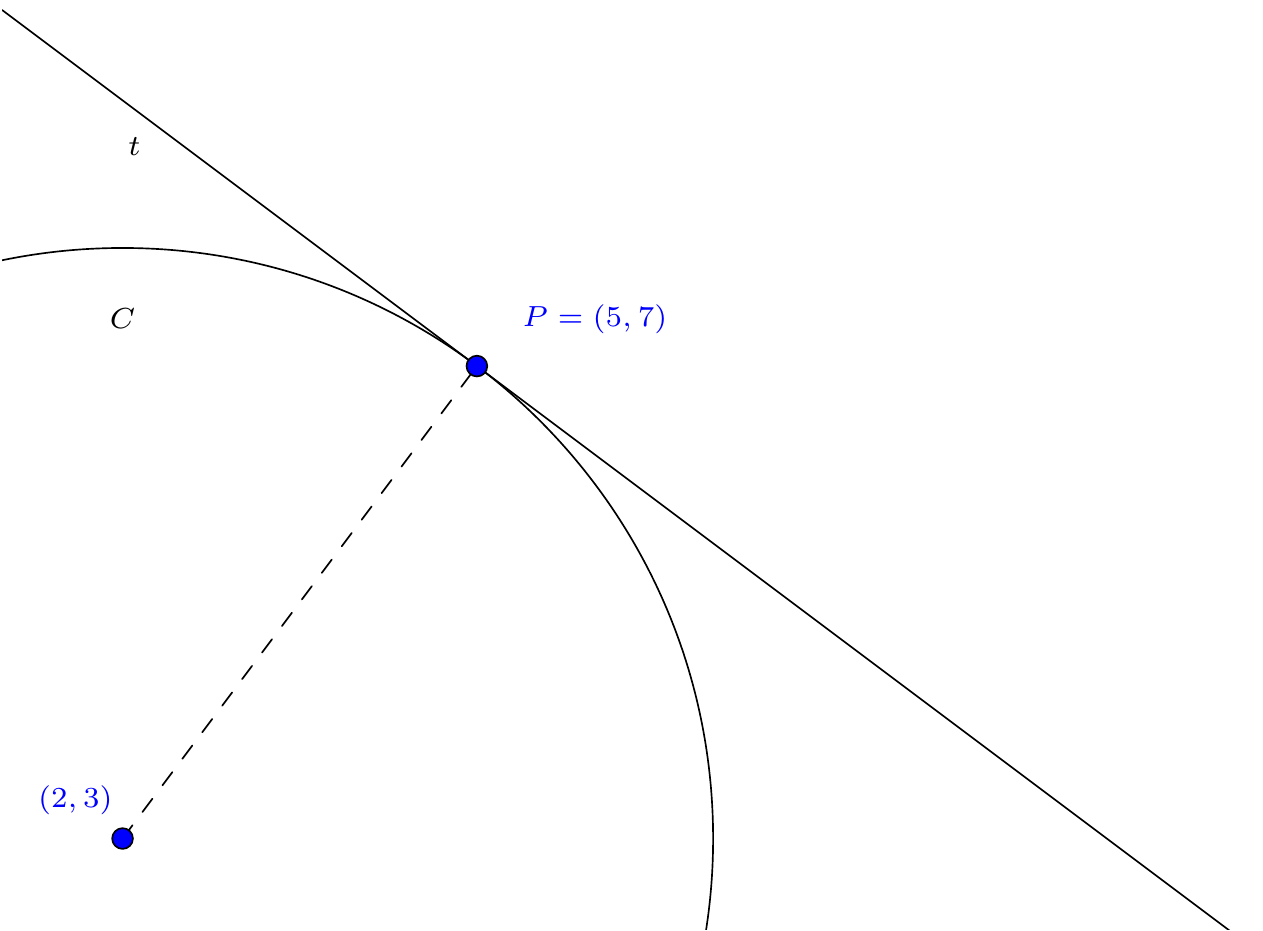

Show that \(P(5,7)\) lies on \(C\) and find the equation of the tangent at \(P\).

Show that the line \(3x-4y+31=0\) is a tangent to \(C\).

\(C\) has equation \[(x-2)^2+(y-3)^2=25.\] Since \((5-2)^2+(7-3)^2=9+16=25\), it follows that \(P\) lies on \(C\).

The tangent \(t\) is perpendicular to the radius at \(P\). This radius has slope \(\dfrac{7-3}{5-2}=\dfrac{4}{3}\), so \(t\) has slope \(-3/4\), and the equation of \(t\) is \(y=-3/4x+c\). Since \((5,7)\) lies on \(t\), we have \(7=-3/4(5)+c\), and so \(c=\frac{43}{4}\). Thus the equation of t is \(3x+4y=43\).

Figure 7.5: The tangent to the circle at the point

- The line \(3x-4y+31=0\) rearranges to \(y=\frac{1}{4}(3x+31)\), and this meets \(C\) when \[(x-2)^2+\left(\frac{1}{4}(3x+31)-3\right)^2=5^2.\] This equation reduces to \((x+1)^2=0\), so \(x=-1\) is a double root. Then the line is a tangent to \(C\) at \((-1,7)\).

7.1.3 Completing the square

In general, the equation \((x-\alpha)^2+(y-\beta)^2=r^2\) can be written as \[x^2+y^2-2\alpha x-2\beta y+(\alpha^2+\beta^2-r^2)=0,\] which is of the form \[x^2+y^2+2gx+2fy+c=0.\] If the equation is given in this form it is no longer possible to “read-off” directly the coordinates of the centre and the value of \(r\).

Completing the square for both \(x\) and \(y\) gives \[(x+g)^2+(y+f)^2+c-g^2-f^2=0,\] or \[(x+g)^2+(y+f)^2=g^2+f^2-c.\] If \(g^2+f^2-c\ge0\) then we get the equation of a circle with centre \((-g,-f)\) and radius \(\sqrt{g^2+f^2-c}\).

Example 7.3 Verify that an equation \[x^2+4x+y^2-5y-2=0\] describes a circle, and find its centre and radius.

Completing the square for both \(x\) and \(y\), we get \[(x+2)^2-4+\left(y-\frac{5}{2}\right)^2-\frac{25}{4}-2=0,\] i.e., \[(x+2)^2+\left(y-\frac{5}{2}\right)^2=\frac{49}{4},\] so we see that this is a circle with centre \((-2,\frac{5}{2})\) and radius \(\frac{7}{2}\).7.1.4 Tangents to circle from a point outside the circle

Figure 7.6: Tangents to a circle from a point outside

Example 7.4 Find the equation of the tangents to the circle \[(x-1)^2+(y-2)^2=2^2\] from the point \(P(5,6)\).

Note: We can easily check that \(P\) is outside the circle: \[(5-1)^2+(6-2)^2=32>2^2.\]

We can differentiate implicitly to find the slope of the circle at a point \(Q(x,y)\): \[2(x-1)+2(y-2)\frac{dy}{dx}=0,\] so \(\frac{dy}{dx}=-\frac{x-1}{y-2}\). The slope of \(QP\) is \(\dfrac{y-6}{x-5}\). So \(-\frac{x-1}{y-2}=\frac{y-6}{x-5}\), which reduces to \[\begin{equation} x^2-6x+y^2-8y+17=0. \tag{7.1} \end{equation}\] The equation of the circle is \[\begin{equation} x^2-2x+y^2-4y+1=0. \tag{7.2} \end{equation}\] (7.1) \(-\) (7.2) gives \(x+y-4=0\) or \(x=4-y\). From (7.2) or (7.1) \((4-y)^2-2(4-y)+y^2-4y+1=0\), so \(2y^2-10y+9=0\), and so \(y=\frac{5}{2}\pm\frac{1}{2}\sqrt{7}\), so that \(x=4-y=\frac{3}{2}\mp\frac{1}{2}\sqrt{7}\).

Now find the equation of the line through \((\frac{3}{2}-\frac{1}{2}\sqrt{7},\frac{5}{2}+\frac{1}{2}\sqrt{7})\) and \((5,6)\) from \(\frac{y-6}{x-5}=\frac{\frac{5}{2}+\frac{1}{2}\sqrt{7}-6}{\frac{3}{2}-\frac{1}{2}\sqrt{7}-5}\), which gives \[\left(-\frac{7}{2}-\frac{1}{2}\sqrt{7}\right)y+\left(\frac{7}{2}-\frac{1}{2}\sqrt{7}\right)x=-\frac{7}{2}-\frac{11\sqrt{7}}{2}.\] Similarly, the line through \((\frac{3}{2}+\frac{1}{2}\sqrt{7},\frac{5}{2}-\frac{1}{2}\sqrt{7})\) is found to be \[\left(-\frac{7}{2}+\frac{1}{2}\sqrt{7} \right)y+\left(\frac{7}{2}+\frac{1}{2}\sqrt{7}\right)x=-\frac{7}{2}+\frac{11\sqrt{7}}{2}.\]

7.1.5 Intersection of two circles

In general two circles may meet at two points, one point or no points (again, think about this geometrically).

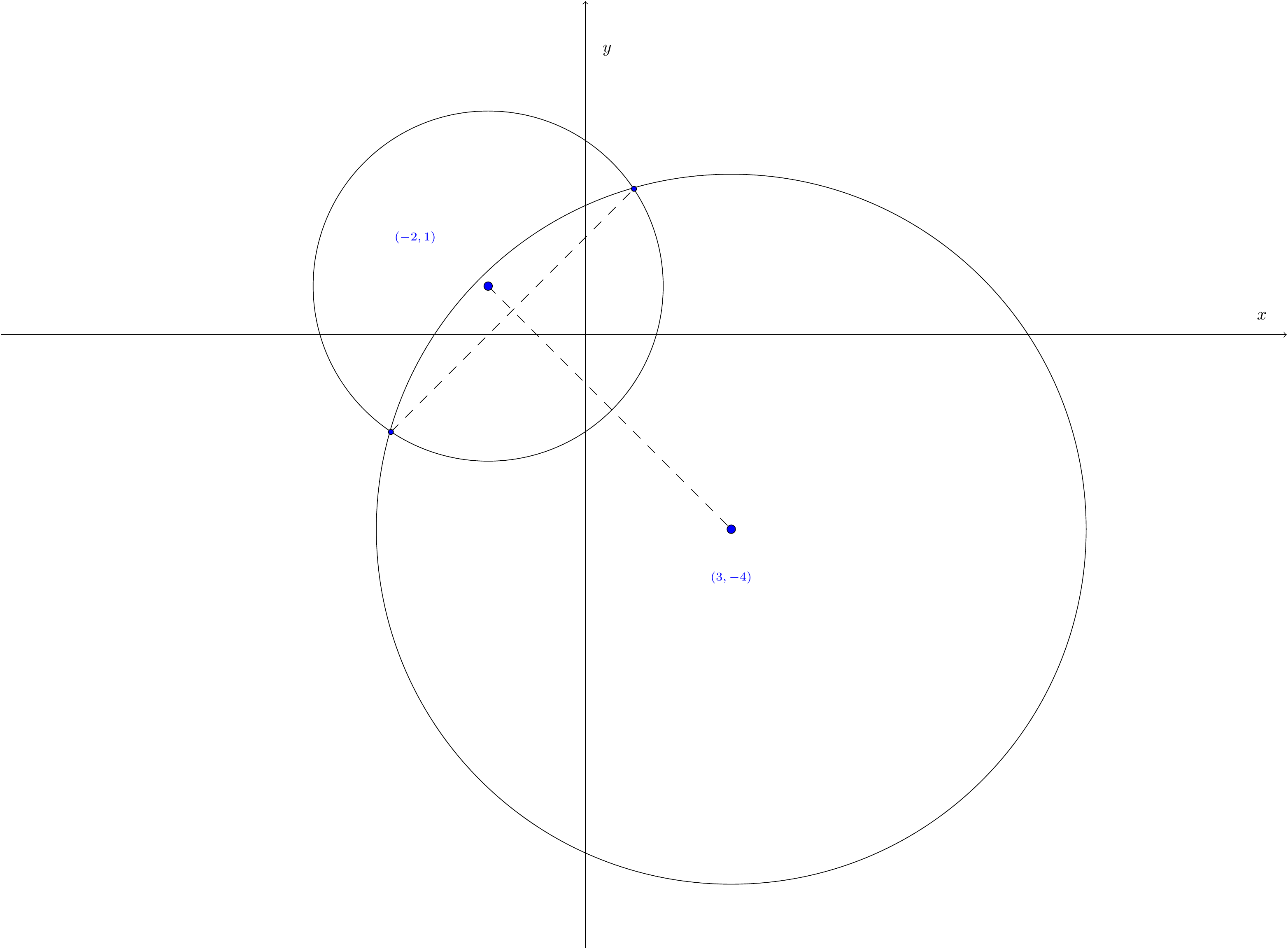

Example 7.5 Consider the two circles \[\begin{aligned} (x-3)^2+(y+4)^2&=53,\\ (x+2)^2+(y-1)^2&=13.\end{aligned}\] Determine their intersection points and a line joining them.

Multiplying out, we have \[\begin{aligned} x^2-6x+y^2+8y-28&=0,\\ x^2+4x+y^2-2y-8&=0.\end{aligned}\] The difference of these is \(-10x+10y-20=0\), or \(y=x+2\).

The intersection points of the two circles are found by locating where the line meets either of the circles. For example, from the first equation, we get \(x^2-6x+(x+2)^2+8(x+2)-28=0\), which simplifies to \(2x^2+6x-8=0\), i.e., to \[x^2+3x-4=0.\] This factorises as \((x+4)(x-1)=0\), with roots \(x=-4\) and \(x=1\), so the line must cut the circle at \((-4,-2)\) and \((1,3)\), and it is easy to see that the line is \(y=x+2\), with slope \(1\). (Think about why this line is always perpendicular to the line joining the centres.)

Figure 7.7: Two intersecting circles

7.1.6 The circle given in parametric form

In Cartesian form, our general circle is \[(x-\alpha)^2+(y-\beta)^2=r^2\] and we can represent our points using trigonometric functions: \[\begin{aligned} AQ&=x-\alpha=r\cos\theta,\\ PQ&=y-\beta=r\sin\theta.\end{aligned}\]

Figure 7.8: Parametrising the circle

Hence \(x=\alpha+r\cos\theta\), \(y=\beta+r\sin\theta\) is the parametric form of the circle.

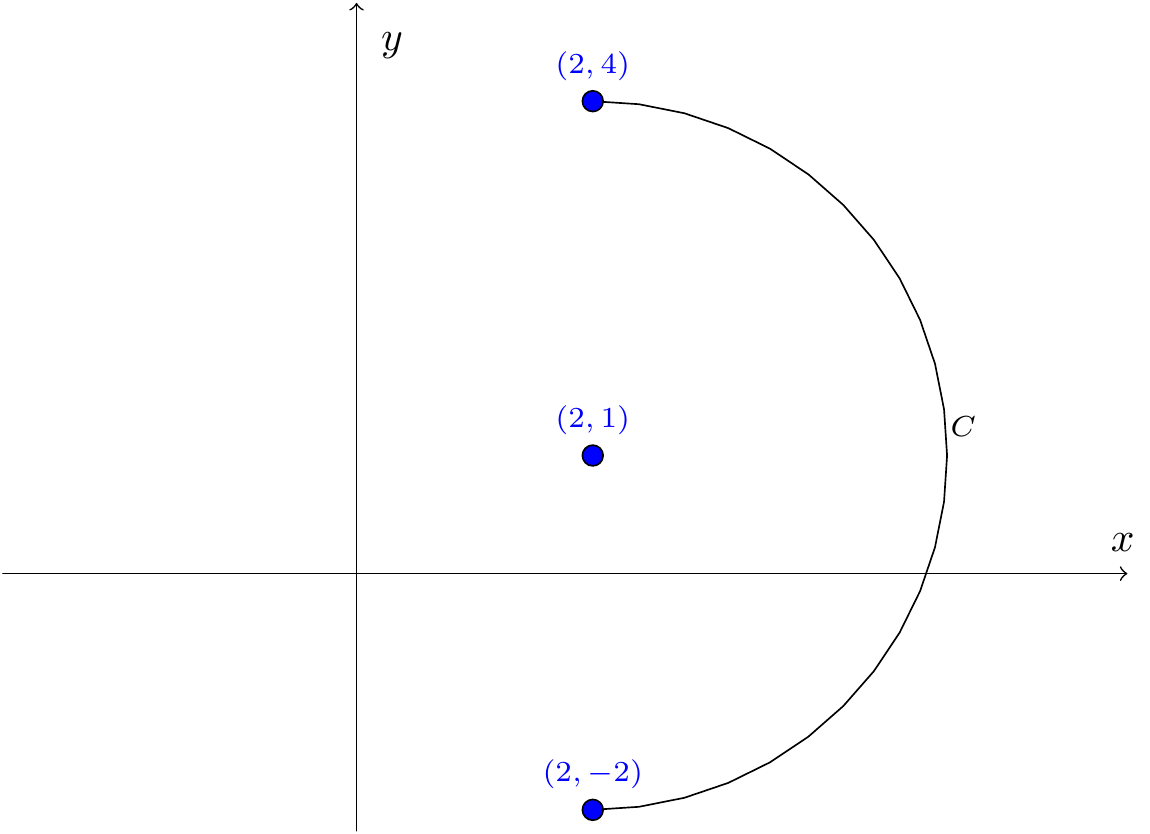

Example 7.6 Use the parametric form to represent just one revolution around the circle with the centre \((2,1)\) and radius \(3\).

\(x=2+3\cos\theta\), \(y=1+3\sin\theta\) as \((0\le\theta\le2\pi)\). (Note that other ranges of length \(2\pi\) are equally valid, e.g., \(-\pi\le\theta\le\pi\).)

Figure 7.9: The semicircle in the example

\(x=2+3\cos\theta\), \(y=1+3\sin\theta\) with \((-\frac{1}{2}\pi\le\theta\le\frac{1}{2}\pi)\). Note here that the precise range of length \(\pi\) is determined by thinking about the start and end points of the semicircular arc.

Example 7.8 The parametrisation representing motions in a circular path is \(x=\alpha+r\cos kt\), \(y=\beta+r\sin kt\) with \(\tau_1\le t\le\tau_2\). Here \(t\) represents time and the constant \(k\) determines the rate and direction of the motion.

Two-circle compound motion describes the position of a point determines simultaneously by two circles. An example is the motion of a fairground ride.

Figure 7.10: Two-circle compound motion

\(C\) goes round the circle \((R\cos Kt,R\sin Kt)\). The motion of \(P\) about \((0,0)\) is given by \[\begin{aligned} x&=R\cos Kt+r\cos kt,\\ y&=R\sin Kt+r\sin kt.\end{aligned}\] It is far simpler to determine the coordinates of \(P\) using the parametric form than the Cartesian form.

7.2 Conic sections

Figure 7.11: The double cone

Consider the double cone shown in the diagram, joined at the vertex. These cones are right circular cones in the sense that slicing the double cones with planes at right-angles to the axis gives cross section which are circular:

Figure 7.12: A circular cross section

Now consider starting with a horizontal slicing plane and tilting it slightly. We obtain an oval curve called an ellipse.

Figure 7.13: An elliptical cross section

Suppose now that the slicing plane has the same slope as the surface of the cone that does not pass through the vertex. In this case we obtain a parabola.

Figure 7.14: A parabolic cross section

If we tilt the slicing plane further so that it cuts both cones, we obtain a hyperbola.

Figure 7.15: A hyperbolic cross section

There are other trivial (degenerate) cases which give point and straight line intersections.

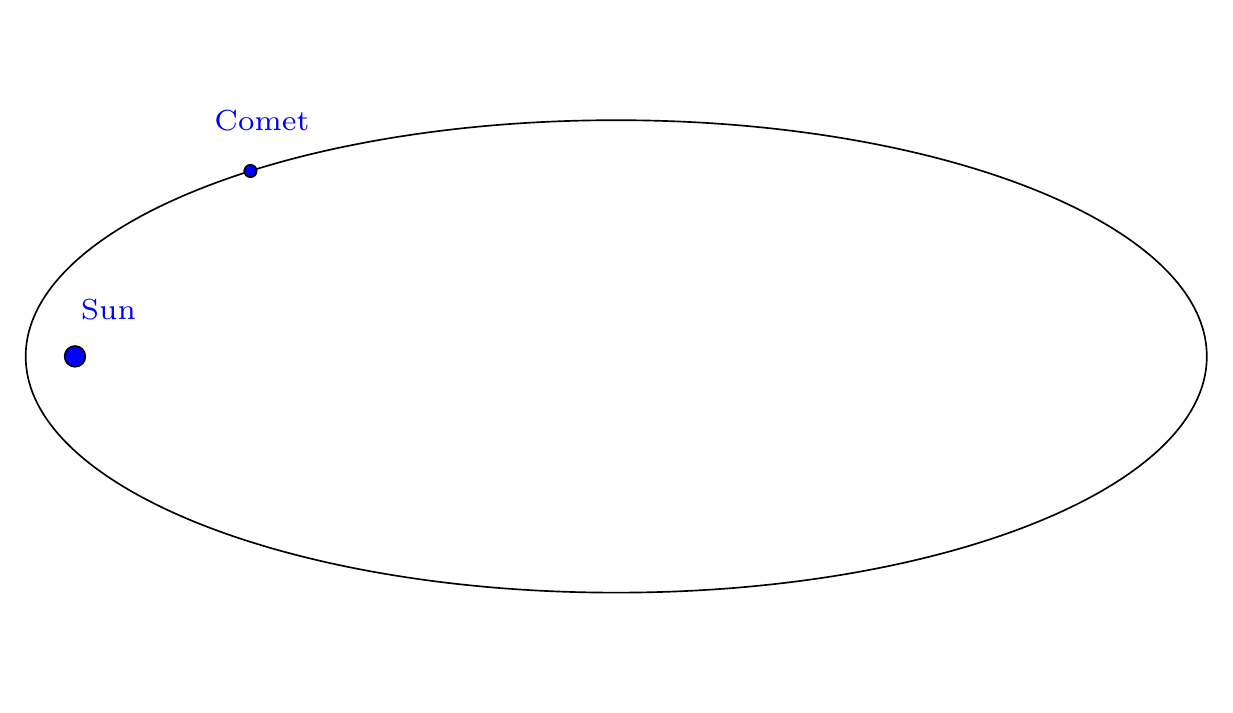

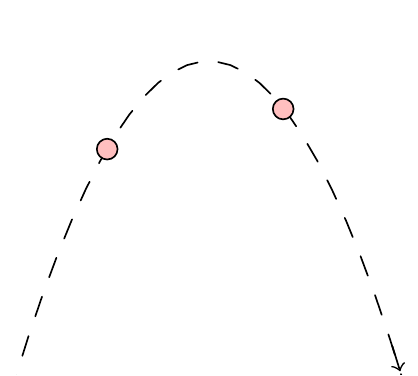

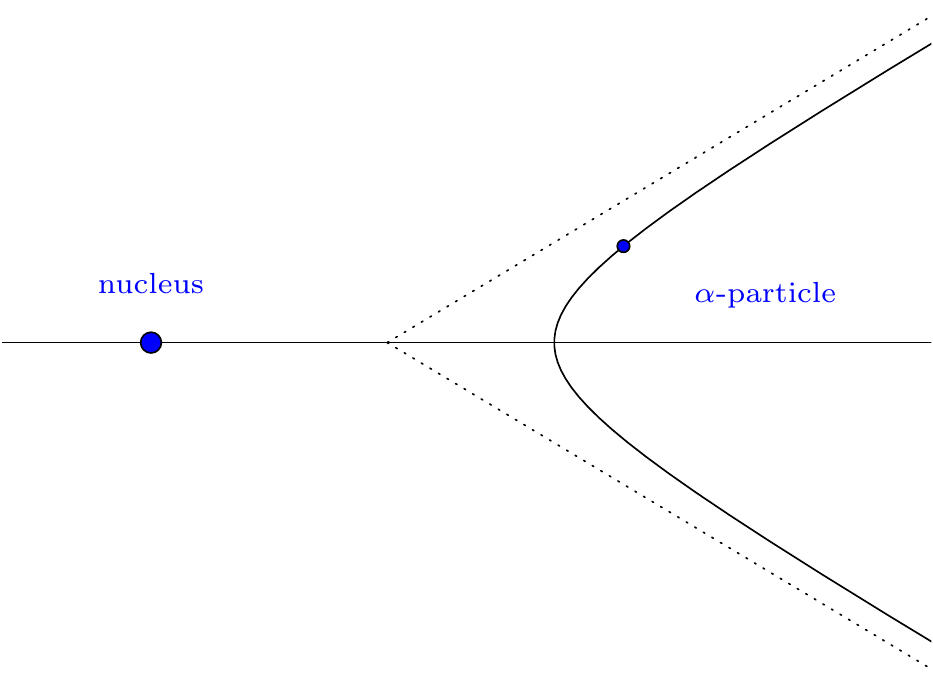

These curves turn up in various areas of mathematics and physics. For example, the motion of planets and comets around the sun follow an elliptical orbit, the path turned out by a particle (e.g., a ball) moving under gravity (ignoring air resistance) is a parabola, the path of an alpha particle moving near to the nucleus of an atom is a hyperbola.

Figure 7.16: Elliptical planetary motion

Figure 7.17: Parabolic projectile motion

Figure 7.18: Hyperbolic repulsive motion

The details of the derivation of the equations of conics are complicated and not useful: we will simply state the standard equations of these curves in a suitable \((x,y)\) coordinate system in the slicing plane.

7.3 Parabolas

The standard equation for the parabola is \(y^2=4ax\), where \(a>0\) is a constant. In general, the parabola with equation \(y^2=4ax\)

meets the axes at \((0,0)\);

is symmetric about the \(x\)-axis;

is unbounded (i.e., as \(x\to\infty\), then \(y\to\pm\infty\)).

The point \((0,0)\) is the vertex of the parabola.

Figure 7.19: The parabola

7.3.1 The focus-directrix property

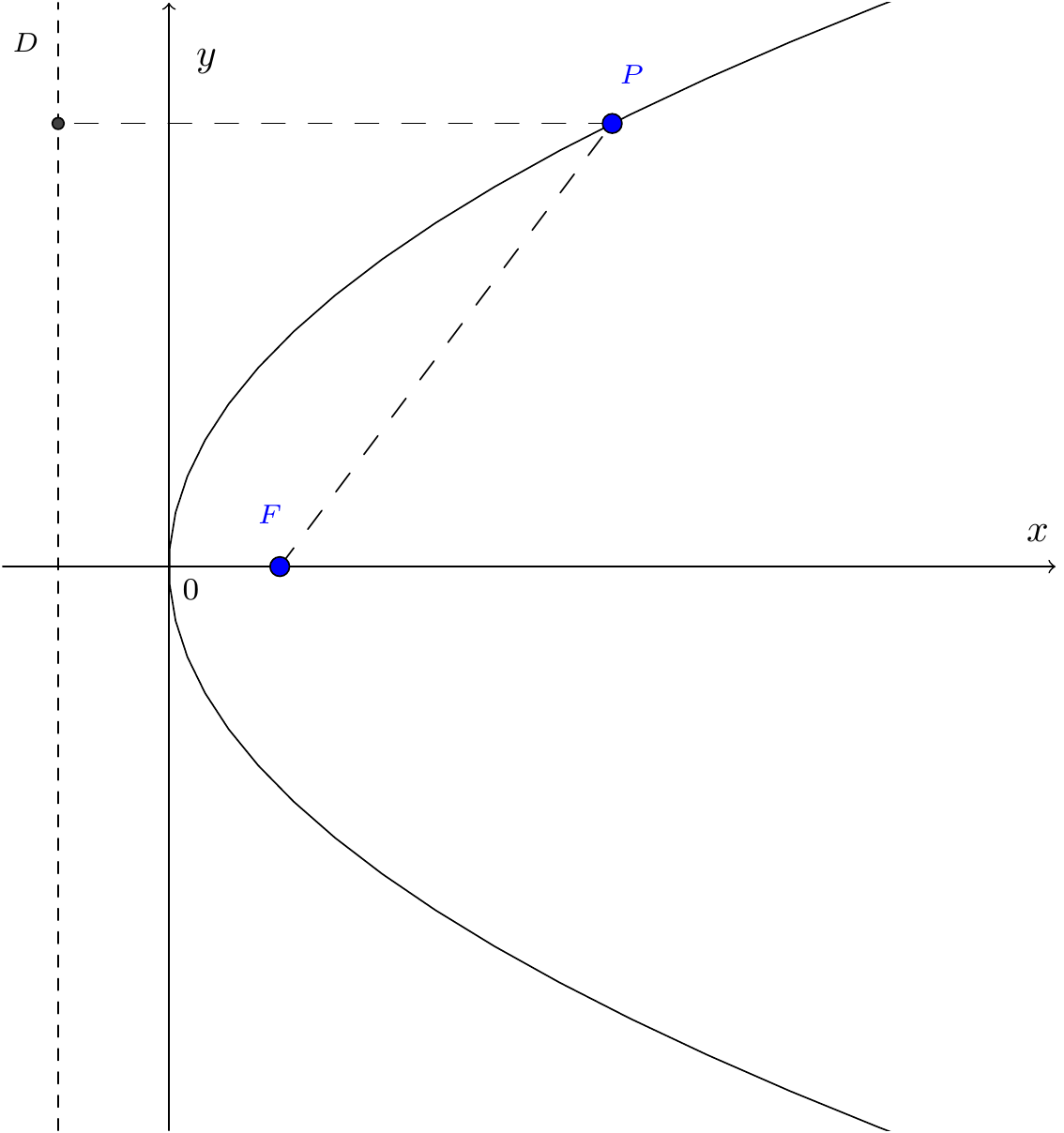

Consider the following diagram, where \(F=(a,0)\), and \(D\) is the line \(x=-a\). We show that the equation of the parabola is the locus of points such that \(|PF|=|PD|\):

Figure 7.20: Focus and directrix for a parabola

\[\begin{aligned} |PF|&=\sqrt{(x-a)^2+y^2},\\ |PD|&=|x+a|.\end{aligned}\] Squaring and equating gives \((x-a)^2+y^2=(x+a)^2\), and this easily reduces to \(y^2=4ax\).

The point \(F(a,0)\) is the focus and the line \(x=-a\) the directrix.

Example 7.9 Find the focus and directrix of the parabola \(y^2=-12x\).

Form \(y^2=-4ax\) with \(a=3\). Thus the focus is \((-3,0)\) and the directrix is \(x=3\).Similarly, the parabola \(x^2=4ay\) has focus \((0,a)\) and directrix \(y=-a\). We can translate the graphs so that the centre is different from \((0,0)\):

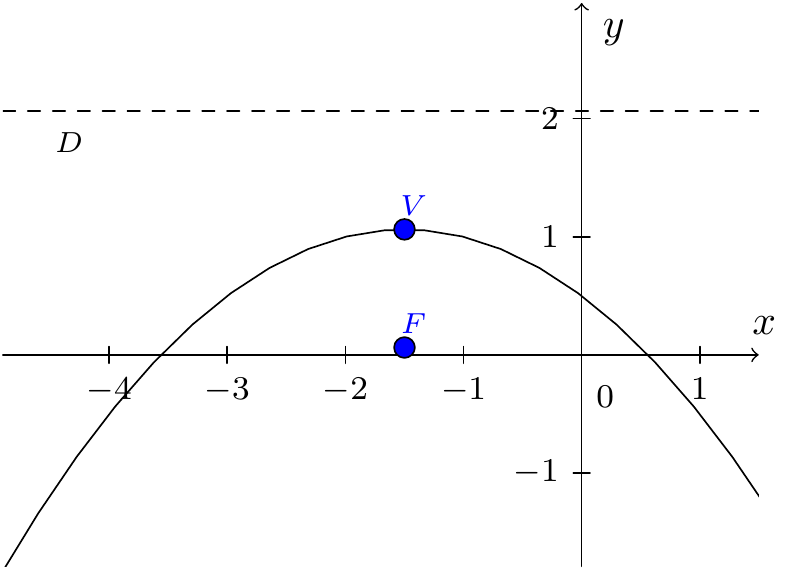

Example 7.10 Find the vertex, focus, directrix and axis of \(x^2=-4y-3x+2\).

Write this as \(x^2+3x=-4y+2\) and complete the square: \[\left(x+\frac{3}{2}\right)^2=-4y+2+\frac{9}{4}.\] This means that \[\left(x+\frac{3}{2}\right)^2=-4\left(y-\frac{17}{16}\right),\] which is of the form \(X^2=-4AY\) with \(A=1\), \(X=x+\frac{3}{2}\), and \(Y=y-\frac{17}{16}\). So the vertex is at \((X,Y)=(0,0)\) i.e., \[(x,y)=\left(-\frac{3}{2},\frac{17}{16}\right).\] The focus is at \((X,Y)=(0,-A)\), or \((x,y)=\left(-\frac{3}{2},\frac{1}{16}\right)\). Finally, the directrix is at \(Y=A=1\), i.e., at \(y=\frac{33}{16}\).

Figure 7.21: Parabola in the previous example

7.3.2 Tangent at a point on the parabola

Example 7.11 Find the equation of the tangent to \(y^2=20x\) at the point \((3,2\sqrt{15})\).

(Check: when \(x=3\), \(y^2=60\), so \(y=\pm2\sqrt{15}\).)

Differentiating \(y^2=20x\) implicitly gives \(2y\frac{dy}{dx}=20\), so \(\frac{dy}{dx}=\frac{10}{y}\). At \((3,2\sqrt{15})\) then \(\frac{dy}{dx}=\frac{5}{\sqrt{15}}\). Hence \(y=\frac{5}{\sqrt{15}}x+c\), and \(c=\sqrt{15}\), so the tangent is given by \(y=\frac{5}{\sqrt{15}}x+\sqrt{15}\).7.3.3 Tangent to parabola from a point not on the parabola

As in the case of circles, there will be either two solutions or no solutions, depending whether the point is “outside” or “inside” the parabola.

Figure 7.22: Tangents to the parabola

Example 7.12 Find the equations of the tangents to the parabola \(y^2-y-2x+4=0\) which pass through \((-5,2)\).

The slope of the curve at any point is given by \(2y\frac{dy}{dx}-\frac{dy}{dx}-2=0\), or \[\frac{dy}{dx}=\frac{2}{2y-1}.\] The line through \((-5,2)\) has equation \(y-2=m(x+5)\), so that \(m=\frac{y-2}{x+5}\). Hence \[\frac{y-2}{x+5}=\frac{2}{2y-1},\] or \[\begin{equation} 2y^2-5 y-2x-8=0. \tag{7.3} \end{equation}\] The equation of the parabola is \[\begin{equation} y^2- y-2x+4=0. \tag{7.4} \end{equation}\] $$ Eliminating \(x\) by (7.3)—(7.4) gives \(y^2-4y-12=0\). Then \((y-6)(y+2)=0\) so that \(y=6\), or \(y=-2\).

When \(y=6\), \(2x=2(36)-30-8\), so \(x=17\), and similarly when \(y=-2\), \(x=5\). The slopes are given by \[\frac{2}{12-1}=\frac{2}{11},\qquad\frac{2}{-4-1}=-\frac{2}{5},\] and so the tangents are \[y-2=\frac{2}{11}(x+5),\qquad y-2=-\frac{2}{5}(x+5).\]7.3.4 Reflection property of the parabola

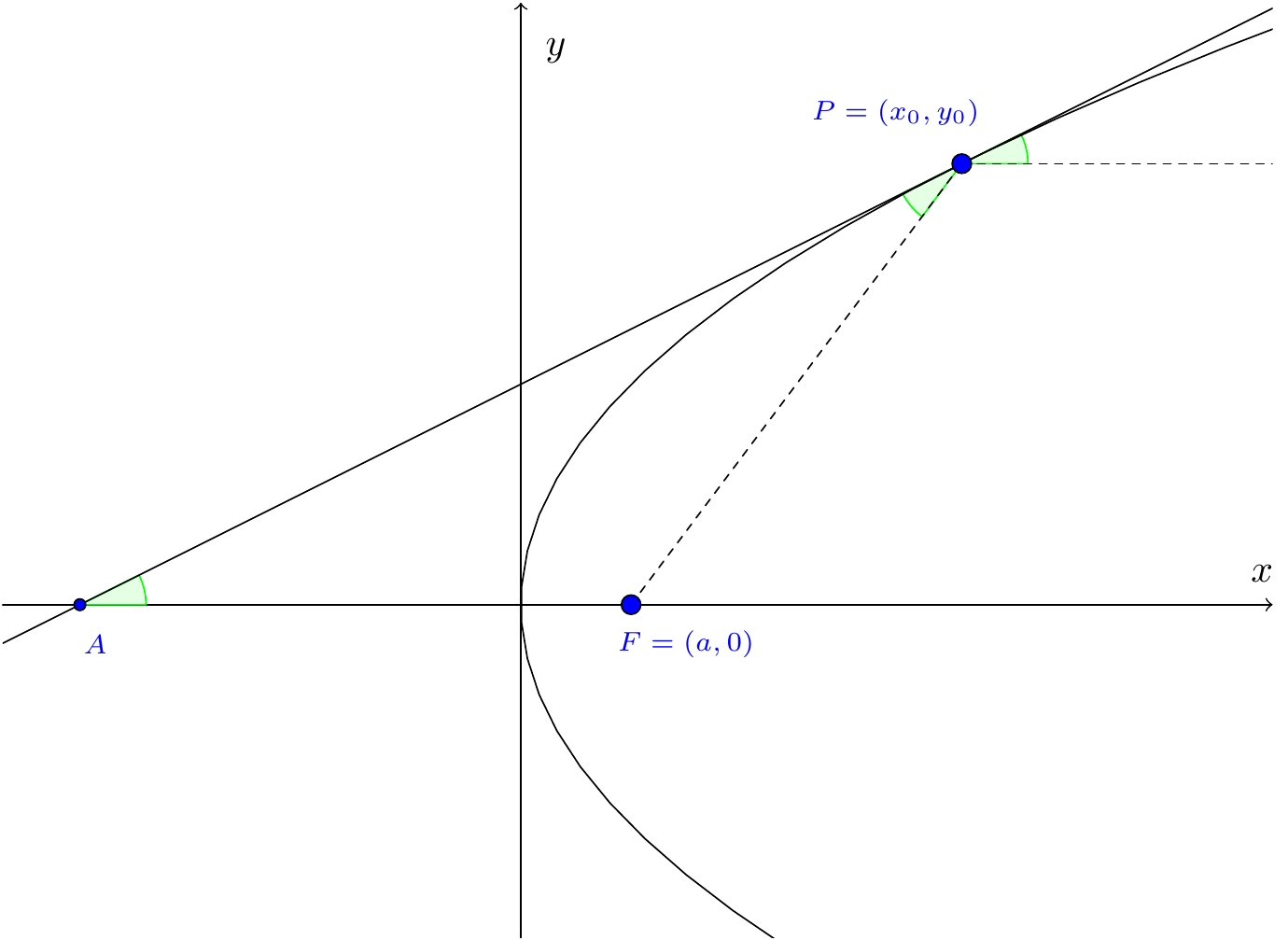

Let \(P(x_0,y_0)\) be any point on the parabola \(y^2=4ax\), with focus \(F(a,0)\).

Figure 7.23: Reflection property for a parabola

Then the angle between \(FP\) and the tangent at \(P\) is the same as the angle between the tangent at \(P\) and the \(x\)-axis. Let’s check this: \(\frac{dy}{dx}=\frac{2a}{y}\), and so \(\frac{dy}{dx}=\frac{2a}{y_0}\) at \((x_0,y_0)\). The equation of the tangent at \(P\) is \(y-y_0=\frac{2a}{y_0}(x-x_0)\). This line meets the \(x\)-axis at \(A\) where \(x=-\frac{y_0^2}{2a}+x_0=-2x_0+x_0=-x_0\), so \(A=(-a,0)\), and so \(AF=x_0+a\). Further, \[PF=\sqrt{(x_0-a)^2+y_0^2}=\sqrt{x_0^2-2ax_0+a^2+4ax_0}=x_0+a=AF.\] Thus \(AFP\) is an isosceles triangle and the stated result follows.

Hence a ray of light originated from the focus \(F\) is reflected parallel to the axis of the parabola.

If a parabola is revolved about its axis the surface generated is called a paraboloid. Such surfaces are used in headlights, optical and radio telescopes, radar etc. The reflection property means that beams of light parallel to the axis of rotation are all reflected to the focus.

Figure 7.24: The paraboloid

7.3.5 Parametric form of the parabola

The standard parametrisation is \(x=at^2\), \(y=2at\) (note that eliminating \(t\) recovers \(y^2=4ax\)).

Note that positive values of \(t\) give points \((x,y)\) on the upper arm of the parabola, whereas negative values of \(t\) give points on the lower arm.

7.4 Ellipses

An ellipse is obtained when the slicing plane is less steep than the surface of the cone. Its standard equation is \[\frac{x^2}{a^2}+\frac{y^2}{b^2}=1,\] where \(a,b>0\). If \(a>b\) we have \((-a,0)\), \((a,0)\), \((0,-b)\) and \((0,b)\) are vertices, and the major axis goes from \((-a,0)\) to \((a,0)\), while the minor axis goes from \((0,-b)\) to \((0,b)\). If \(a<b\), then the major and minor axes are exchanged – the major axis is the longer one.

Figure 7.25: The ellipse

(If \(a=b\) the equation represents the circle \(x^2+y^2=a^2\).)

The \(x\)- and \(y\)-axes are the axes of symmetry of the ellipse in standard position.

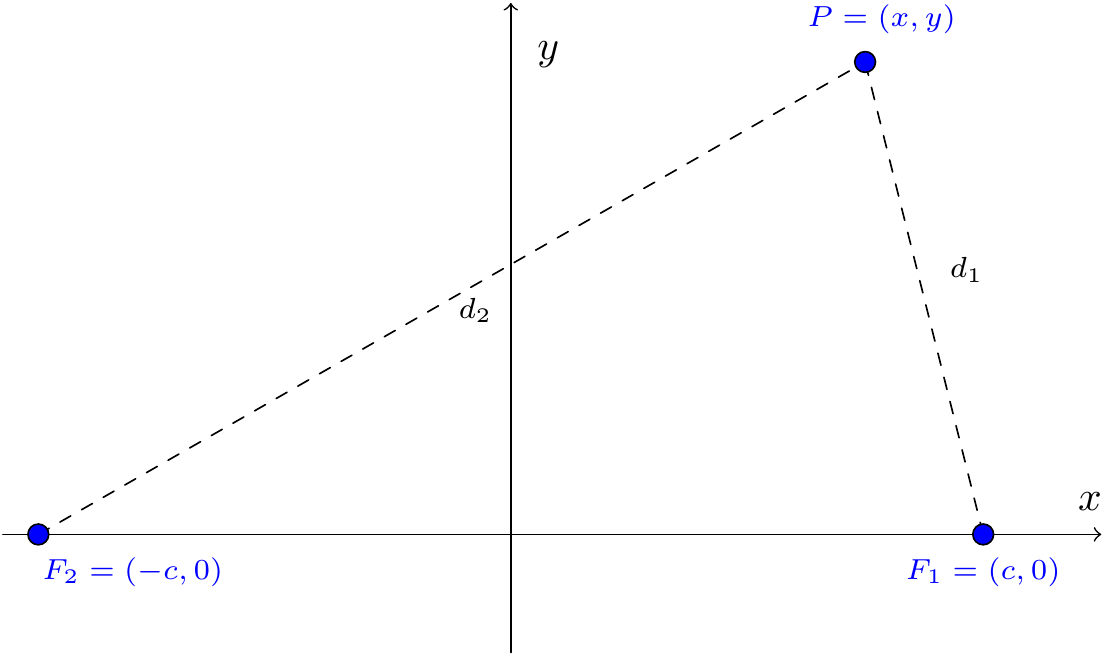

It turns out that an ellipse is the locus all points the sum of whose distances from two fixed points is constant. The two fixed points are called foci. Let’s verify this in the case where \(F_1(c,0)\) and \(F_2(-c,0)\).

Figure 7.26: A point on the ellipse and the two foci

Thus \(d_1+d_2\) is equal to some constant, \(2a\), say, where \(2a>2c\). Hence \[\sqrt{(x-c)^2+(y-0)^2}+\sqrt{(x+c)^2+(y-0)^2}=2a.\] Then \[(x-c)^2+y^2=4a^2-4a\sqrt{(x+c)^2+y^2}+(x+c)^2+y^2\] giving \[-4cx=4a^2-4a\sqrt{(x+c)^2+y^2}\] or \[\sqrt{(x+c)^2+y^2}=a+\frac{c}{a}x.\] Thus \[(x+c)^2+y^2=a^2+2cx+\frac{c^2}{a^2}x^2\] which simplifies to \[\left(\frac{a^2-c^2}{a^2}\right)x^2+y^2=a^2-c^2.\] Hence \[\frac{x^2}{a^2}+\frac{y^2}{a^2-c^2}=1;\] by letting \(b^2=a^2-c^2\), we have \[\frac{x^2}{a^2}+\frac{y^2}{b^2}=1.\] This construction allows an ellipse to be drawn via pencil, string etc. – the “geometric” method. The eccentricity of an ellipse is defined as \(e=\frac{c}{a}\), so that the foci are at \((\pm ae,0)\), and since \(c^2=a^2-b^2\) \[e=\sqrt{1-\frac{b^2}{a^2}}.\] Clearly \(0<e<1\). For a nearly circular ellipse \(e\) is close to 0, whereas for a very squashed ellipse \(e\) is close to 1.

Example 7.13

Find the equations of the ellipse satisfying

Vertices at \((\pm 6,0)\), eccentricity \(\dfrac{2}{3}\);

Foci at \((0,\pm 4)\), eccentricity \(4/5\).

\(a=6\), \(2/3=\sqrt{1-b^2/36}\) and this gives \(b^2=20\). Hence \[\frac{x^2}{36}+\frac{y^2}{20}=1.\]

The foci \((0,\pm4)\) are on the \(y\)-axis, hence the major axis is along the \(y\)-axis. Here it is essential to retain \(a\) for the major and \(b\) for the minor axis for our formula to be valid. Hence \(4=ae=\frac{4}{5}a\), and so \(a=5\). Then \(\frac{4}{5}=\sqrt{1-\frac{b^2}{25}}\), which gives \(b^2=9\), or \(b=3\). Thus, the equation is \(\frac{x^2}{9}+\frac{y^2}{25}=1\).

7.4.1 Tangent at a point on the ellipse

Example 7.14 Find the equation of the tangent at the point \((2,-1)\) on the ellipse \(x^2+2y^2=6\).

Differentiating implicitly gives \(2x+4y\frac{dy}{dx}=0\), so that \(\frac{dy}{dx}=-\frac{x}{2y}\). At \((2,-1)\), \(\dfrac{dy}{dx}=1\). Hence the tangent is \(y-(-1)=1(x-2)\) or \(x-y-3=0\).7.4.2 Tangent from a point outside the ellipse

Example 7.15 Find the equations of the lines through \((1,4)\) which are tangents to the ellipse \(x^2+2y^2=6\).

The equation of the line through \((1,4)\) with gradient \(m\) is \(y-4=m(x-1)\).

Figure 7.27: Tangents to the ellipse from a point outside

The line \(y=mx-(m-4)\) meets the ellipse when \[x^2+2[mx-(m-4)]^2=6,\] or \[\begin{equation} (1+2m^2)x^2-4m(m-4)x+2m^2-16m+26=0. \tag{7.5} \end{equation}\] As each tangent meets the ellipse in exactly one point we look for repeated roots of this equation. Hence we require \[[4m(m-4)]^2-4(1+2m^2)(2 m^2-16m+26)=0\] or \(5m^2+8m-13=0\), which factorises as \((5m+13)(m-1)=0\). Thus \(m=-\frac{13}{5}\) or \(1\). Thus the tangents are \(y-4=-\frac{13}{5}(x-1)\) (i.e., \(13x+5y=33\)) and \(y-4=x-1\) (i.e., \(x-y=-3\)).

Let’s work out what the tangent points actually are on the ellipse in the last example. From (7.5) with \(m=1\), we find \(3x^2+12x+12=0\), which gives \((x+2)^2=0\), so that \(x=-2\) and then \(y=3+(-2)=1\).

With \(m=-13/5\), we get \(363x^2-1716x+2028=0\), which gives \(121x^2-572x+676=0\), and this must have a double root; indeed, it factorises as \((11x-26)^2=0\), and then \(x=\frac{26}{11}\). Then it follows that \(y=\frac{5}{11}\).

7.4.3 The focus-directrix property

Figure 7.28: The focus-directrix property for an ellipse

Here we show that \(|PF_1|=e|PD_1|\) where \(D_1\) is on the line \(x=\frac{a}{e}\). The equation of the ellipse is \[\frac{x^2}{a^2}+\frac{y^2}{a^2(1-e^2)}=1,\] as \(b^2=a^2(1-e^2)\), so \[x^2(1-e^2)+y^2=a^2(1-e^2)\] and so \[x^2+a^2e^2+y^2=a^2+e^2x^2.\] Subtracting \(2aex\) from both sides, we have \[(x-ae)^2+y^2=(a-ex)^2=e^2\left(\frac{a}{e}-x\right)^2.\] Now \(|PF_1|=\sqrt{(x-a e)^2+y^2}\) and \(|PD_1|=\dfrac{a}{e}-x\) if \(D_1\) is on the line \(x=a/e\). Thus \(|PF_1|=e|PD_1|\). Similarly, \(|PF_2|=e|PD_2|\).

7.4.4 The reflection property

Consider a point \(P=(x,y)\) on an ellipse, and the tangent to the ellipse at \(P\). Then consider the angles made by the tangent with the lines joining \(P\) to each focus:

Figure 7.29: The reflection property for an ellipse

It can be shown that \(\alpha=\beta\) (proof omitted). This means that if the ellipse were a mirrored surface then any light emitted at \(F_1\) will reflect onto \(F_2\) and vice versa. The same idea is exploited in the construction of “whispering galleries”.

7.4.5 Parametric equations

The standard parametrisation of the ellipse \[\frac{x^2}{a^2}+\frac{y^2}{b^2}=1\] is \[\begin{aligned} x&=a\cos t,\\ y&=b\sin t,\end{aligned}\] with \(0\le t\le 2\pi\). As \(t\) increases from \(0\) to \(2\pi\) the point \((a\cos t,b\sin t)\) travels once round the ellipse (anticlockwise) starting and finishing at \((a,0)\).

7.5 Hyperbolas

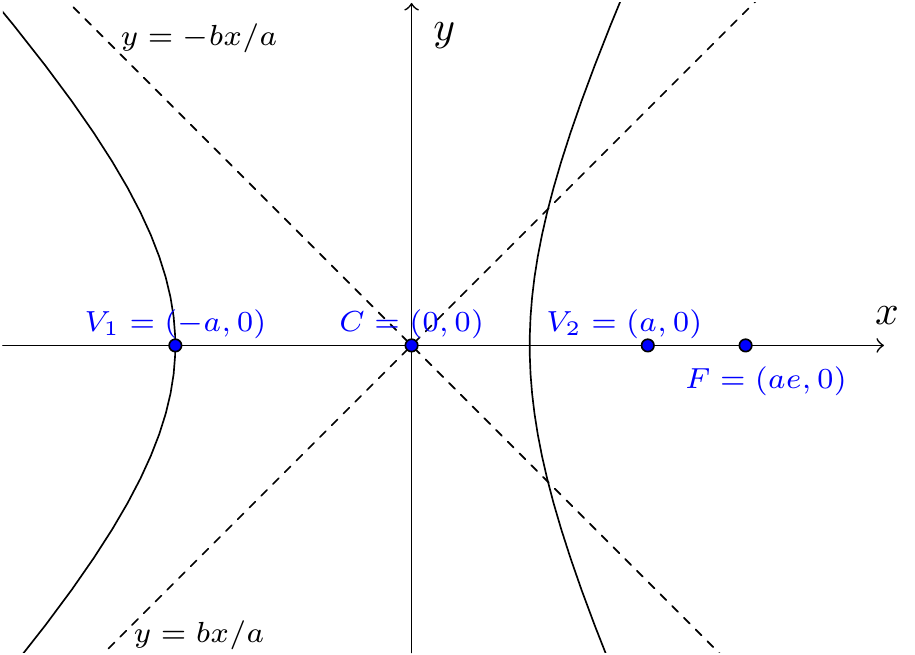

Figure 7.30: The hyperbola and its asymptotes

A hyperbola is obtained when the slicing plane is steeper than the surface of the double cone. The standard equation of the hyperbola is \[\frac{x^2}{a^2}-\frac{y^2}{b^2}=1,\] where \(a,b>0\). There is no requirement that \(a>b\). Writing this in the form \[y^2=b^2\left(\frac{x^2}{a^2}-1\right)=\frac{b^2 x^2}{a^2}\left(1-\frac{a^2}{x^2}\right),\] we find \[y=\pm\frac{bx}{a}\left(1-\frac{a^2}{x^2}\right)^{1/2}.\] As \(x\to\pm\infty\), this tends to the lines \(y=\pm\frac{bx}{a}\), which are the asymptotes of the hyperbola. When \(y=0\), \(x=\pm a\), are the vertices.

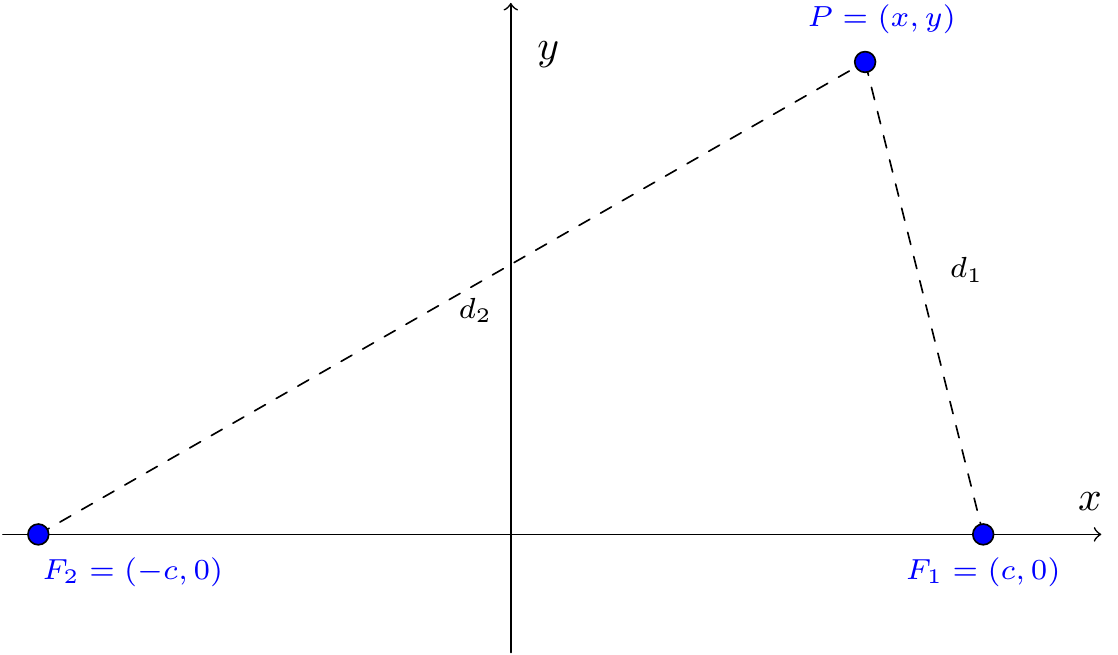

It turns out that a hyperbola is the locus of all points the difference of whose coordinates from two fixed points is a positive constant. The two fixed points are called foci, \(F_1(c,0)\) and \(F_2(-c,0)\).

Figure 7.31: Distance property for a hyperbola

Thus either \(d_1-d_2\) or \(d_2-d_1\) is a positive constant which we call \(2a\), i.e., \(d_1-d_2=\pm2a\). Thus \(\sqrt{(x-c)^2+y^2}-\sqrt{(x+c)^2+y^2}=\pm2a\). Transferring the second square root to the right-hand side and squaring gives \[(x-c)^2+y^2=(x+c)^2+y^2\pm4a\sqrt{(x+c)^2+y^2}+4a^2,\] which reduces to \[\pm4a\sqrt{(x+c)^2+y^2}=4a^2+4cx.\] Dividing by \(4a\) and squaring gives \[x^2+2cx+c^2+y^2=a^2+2cx+\frac{c^2}{a^2}x^2,\] or \[\left(\frac{c^2-a^2}{a^2}\right)x^2-y^2=c^2-a^2.\] Hence \[\frac{x^2}{a^2}-\frac{y^2}{c^2-a^2}=1.\] Recall that the sum of the lengths of any two sides of a triangle must be greater than the length of the third side. Hence \(2c+d_2>d_1\) and \(2c+d_1>d_2\), and thus \(2c>|d_1-d_2|\). But \(|d_1-d_2|=2a\), and so \(c >a\).

We write \(b=\sqrt{c^2-a^2}\) (where \(b>0\)) and hence \[\frac{x^2}{a^2}-\frac{y^2}{b^2}=1.\] The eccentricity of a hyperbola is defined as \(e=\frac{c}{a}\) so that the foci are at \((\pm ae,0)\), and since \(c^2=b^2+a^2\), \[e=\sqrt{1+\frac{b^2}{a^2}}.\] Note that \(e >1\). For a very ‘thin’ hyperbola \(b/a\) is small and \(e\) is close to 1. For a ‘fat’ hyperbola \(b/a\) is very large and hence \(e\) is very large.

Example 7.16

Find the equation of the hyperbola satisfying

vertices at \((\pm5,0)\), foci at \((\pm7,0)\);

vertices at \((0,\pm7)\), eccentricity \(4/3\).

\(a=5\), \(ae=7\), so \(e=7/5\). Put \(\frac{7}{5}=\sqrt{1+\frac{b^2}{25}}\), so that \(\frac{49}{25}=1+\frac{b^2}{25}\), and find \(b^2=24\). Hence \(\frac{x^2}{25}-\frac{y^2}{24}=1\).

Here the foci are on the \(y\)-axis and the equation takes the form \[\frac{y^2}{a^2}-\frac{x^2}{b^2}=1,\] with the vertices \((0,\pm a)\), foci \((0,\pm ae)\) and \(e\) as before. Hence \(a=7\), \(ae=\dfrac{28}{3}\), giving foci at \((0,\pm\frac{28}{3})\). Then \[\frac{16}{9}=1+\frac{b^2}{49},\] so that \(b^2=\frac{343}{9}\), and \(\frac{y^2}{49}-\frac{9x^2}{343}=1\).

7.5.1 Tangent at a point on a hyperbola

Example 7.17 Find the equation of the tangent to the hyperbola \[\frac{x^2}{9}-\frac{y^2}{16}=1\] at the point \((5,-16/3)\) on the hyperbola.

Differentiate: \(\frac{2x}{9}-\frac{2y}{16}\frac{dy}{dx}=0\), so that \(\frac{dy}{dx}=\frac{16x}{9y}\). Then at \((5,-16/3)\), \(\frac{dy}{dx}=-\frac{80}{48}=-\frac{5}{3}\). So the tangent is \(y-\left(-\frac{16}{3}\right)=-\frac{5}{3}(x-5)\), which simplifies to \(3y=-5x+9\).7.5.2 Tangents from a point not on the hyperbola

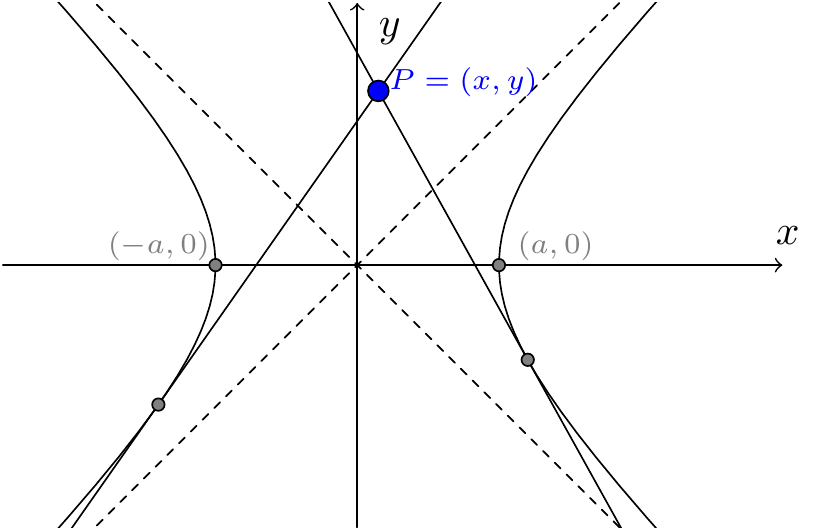

Figure 7.32: Tangents from a point not on the hyperbola

It turns out that we can only construct tangents to a hyperbola from points \(P\) where \(\frac{x^2}{a^2}-\frac{y^2}{b^2}<1\). (This is the region between the two branches of the hyperbola.)

Example 7.18 Find the equations of the tangents from \(P(1,3)\) to the hyperbola \[\frac{x^2}{4}-\frac{y^2}{3}=1.\]

The line through \((1,3)\) with slope \(m\) is \(y-3=m(x-1)\). This line meets the hyperbola at \[\frac{x^2}{4}-\frac{1}{3}\left[mx-(m-3)\right]^2=1,\] or \[(3-4m^2)x^2+8m(m-3)x-4m^2+24m-48=0.\] For repeated roots, \[64m^2(m-3)^2+4(3-4m^2)(4m^2-24m+48)=0,\] which reduces to \(m^2+2m-4=0\), and so \(m=-1\pm\sqrt{5}\). The tangents are \(y-3=(-1\pm\sqrt{5})(x-1)\) which can be written \(y=(-1\pm\sqrt{5})x+4\mp\sqrt{5}\). The points of tangency can be found by intersecting the line and hyperbola for each \(m\). We find that these are at \(\left(\frac{-4\pm12\sqrt{5}}{11},\frac{-12\pm 3\sqrt{5}}{11}\right)\).

7.5.3 The focus-directrix property

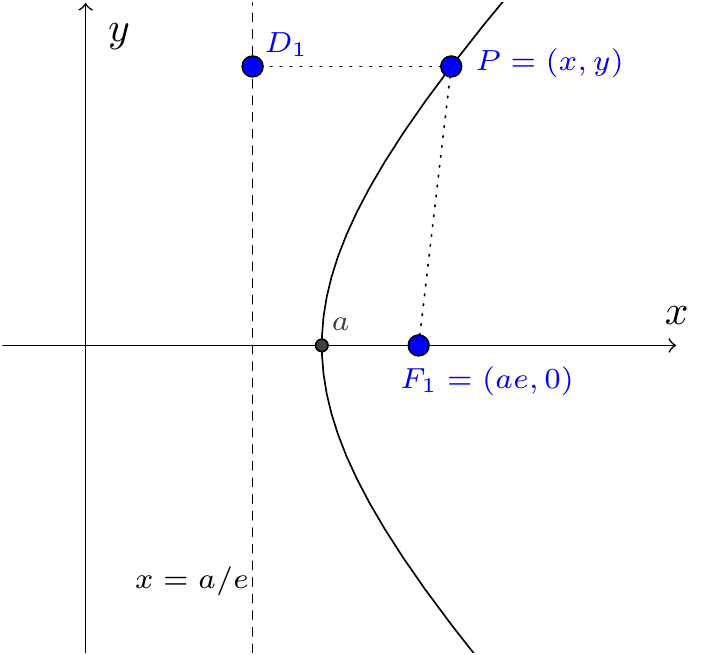

The relationship \(|PF_{1,2}|=e|PD_{1,2}|\) holds as for the ellipse and the equations for the directrix are \(x=\pm\dfrac{a}{e}\).

Figure 7.33: The focus-directrix property for a hyperbola

7.5.4 Reflection property

The reflection of the ray from one focus to a point on the curve, if extended backwards, goes through the other focus \(F_2(-ae,0)\).

Figure 7.34: Reflection property for a hyperbola

(This idea is used in some kinds of telescopes.)

7.5.5 Parametric equations

The standard parametrisation of the hyperbola is \(x=a\sec t\), \(y=b\tan t\), with \(-\frac{1}{2}\pi<t<\frac{1}{2}\pi\), or \(\frac{1}{2}\pi<t<\frac{3}{2}\pi\). As \(t\) increases from \(-\frac{1}{2}\pi\) to \(\frac{1}{2}\pi\), the point \((a\sec t,b\tan t)\) moves upwards along the right-hand branch of the hyperbola. The left-hand branch is obtained as \(t\) increases from \(\frac{1}{2}\pi\) to \(\frac{3}{2}\pi\).

7.5.6 The rectangular hyperbola

If \(b=a\), then the asymptotes are \(y=\pm x\) (intersect at right angles), and the equation can be written \(x^2-y^2=a^2\). It turns out that if we make a change of coordinates so that \(y=-x\) becomes the new \(x\)-axis and \(y=x\) the new \(y\)-axis, the equation has a simpler form.

Figure 7.35: The rectangular hyperbola

Consider the following transformation, which we have already seen represents an (anticlockwise) rotation by \(\theta\): \[\begin{eqnarray*} X&=&x\cos\theta-y\sin\theta,\\ Y&=&x\sin\theta+y\cos\theta. \end{eqnarray*}\] In our case we need to choose \(\theta=\pi/4\), hence \[X=\frac{x-y}{\sqrt{2}},\qquad Y=\frac{x+y}{\sqrt{2}}.\] Thus \[x^2-y^2=(x-y)(x+y)=2XY=a^2.\] Changing the notation we can write \(xy=c^2\) where \(c=a/\sqrt{2}\). The standard parametrisation of \(xy=c^2\) is \(x=ct\), \(y=\frac{c}{t}\), with \(t\ne0\).

Figure 7.36: A more usual form of the rectangular hyperbola

7.5.7 The hyperboloid

Just like the rotation of the parabola around an axis gives the paraboloid, we can do the same for the hyperbola. There are a number of axes that might make sense, but the one which produces shapes you will recognise is the \(y\)-axis. If we rotate \(x^2-y^2=a^2\) around \(x=0\), we get the following shape:

Figure 7.37: The (one sheeted) hyperboloid

You should recognise this shape – it’s the shape used by cooling towers for power stations. It does have some interesting properties; it is a doubly ruled surface, which means that every point on the surface belongs to two straight lines:

Figure 7.38: The hyperboloid as a doubly ruled surface

You might like to try making one yourself! Take two rings (of card?) of equal radii, make equally spaced holes in the same places around the edges, and tie string from each hole in the top ring to a position a fixed number (perhaps 5, 10 or 20, depending on how many holes you have) further around, and further back, on the bottom ring.

I’d also love to have a clear explanation of why cooling towers are designed in a hyperboloid shape – I can see mathematically that the doubly ruled structure should make them very stable, but I don’t know why this makes them good from the point of view of a power station….

7.6 Hyperbolic functions

Hyperbolic functions are related to trigonometric functions, and play quite an important role in various areas of mathematics. In fact, they really deserve much more prominence than we’re giving them in this module! However, they probably fit most easily into the course at this point.

We define the hyperbolic functions as follows (this will introduce some notation you may not have seen before, except as buttons on your calculator!):

Definition 7.1 The hyperbolic sine of \(x\) is defined by \[\sinh x=\frac{e^x-e^{-x}}{2}.\] The hyperbolic cosine of \(x\) is defined by \[\cosh x=\frac{e^x+e^{-x}}{2}.\] We also define the hyperbolic tangent, \(\tanh x\), to be the quotient \(\sinh x/\cosh x\).

Exercise 7.1 Show from the definitions that:

\(\cosh\) is an even function, and \(\sinh\) is an odd function;

\(\cosh^2x-\sinh^2x=1\);

\(\cosh(x+y)=\cosh x.\cosh y+\sinh x.\sinh y\);

\(\sinh(x+y)=\sinh x.\cosh y+\cosh x.\sinh y\);

\(\frac{d}{dx}\sinh x=\cosh x\) and \(\frac{d}{dx}\cosh x=\sinh x\).

The parallel with the usual trigonometric functions should be clear from these formulae; they satisfy exactly the same identities, apart from the change in some signs.

In the same way that the trigonometric functions crop up when solving differential equations of the form \(\frac{d^2y}{dx^2}=-k^2y\), the final claim of Exercise 7.1 shows that the hyperbolic functions \(y=\sinh kx\) and \(y=\cosh kx\) both satisfy \(\frac{d^2y}{dx^2}=k^2y\). So they play a similar role in second order differential equations to the trigonometric functions \(\sin kx\) and \(\cos kx\). (Of course, they are simply linear combinations of \(e^{kx}\) and \(e^{-kx}\), so this shouldn’t be a surprise.)

In the same way that inverse trigonometric functions turn up in the expressions for integrals, so do the inverse hyperbolic functions. We’ll see some examples on the exercise sheets. But let’s draw the graphs:

Figure 7.39: Graphs of the hyperbolic functions

If you suspend a chain, by holding its two ends, it makes the shape of (part of) the graph of \(\cosh x\). For this reason, the graph of \(\cosh x\) is also called the catenary, since the Latin for “chain” is catena.

Note that the equation \(\cosh^2t-\sinh^2t=1\) gives another parametrisation of the hyperbola \(x^2-y^2=1\); this is parametrised by \(x=\cosh t\) and \(y=\sinh t\).

7.7 Quadratic curves

Consider the general quadratic curve \[Ax^2+Bxy+Cy^2+Dx+Ey+F=0,\] with \(A\), \(B\), \(C\) not all zero. Here we focus on the case \(B=0\). By completing the square (if necessary) we can show that such equations often represent non-degenerate conics which are ‘shifted’ or ‘translated’ from the standard position. (We’ve already seen a shifted parabola.)

Example 7.19

Identify the following conics

\(4x^2+9y^2-16x-18y-11=0\);

\(x^2-4y^2-6x-40y-95=0\).

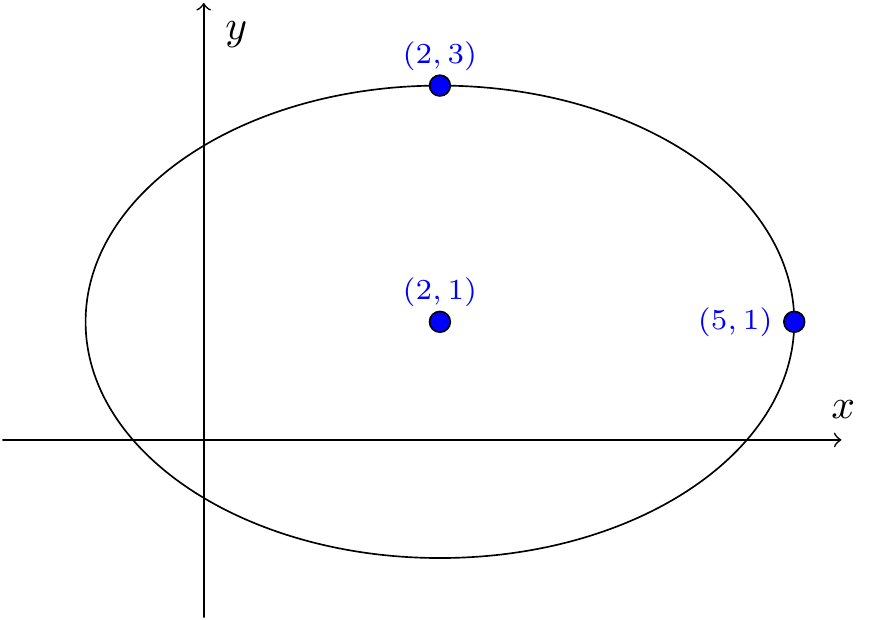

- We group the variables together: \(4(x^2-4x)+9(y^2-2y)-11=0\), and complete the square: \[4[(x-2)^2-4]+9[(y-1)^2-1]-11=0.\] This becomes \(4(x-2)^2+9(y-1)^2=36\), which, after dividing by \(36\), becomes \[\frac{(x-2)^2}{9}+\frac{(y-1)^2}{4}=1,\] and we recognise this as an ellipse with centre \((2,1)\), major axis \(3\), and minor axis \(2\).

Figure 7.40: The first example: an ellipse

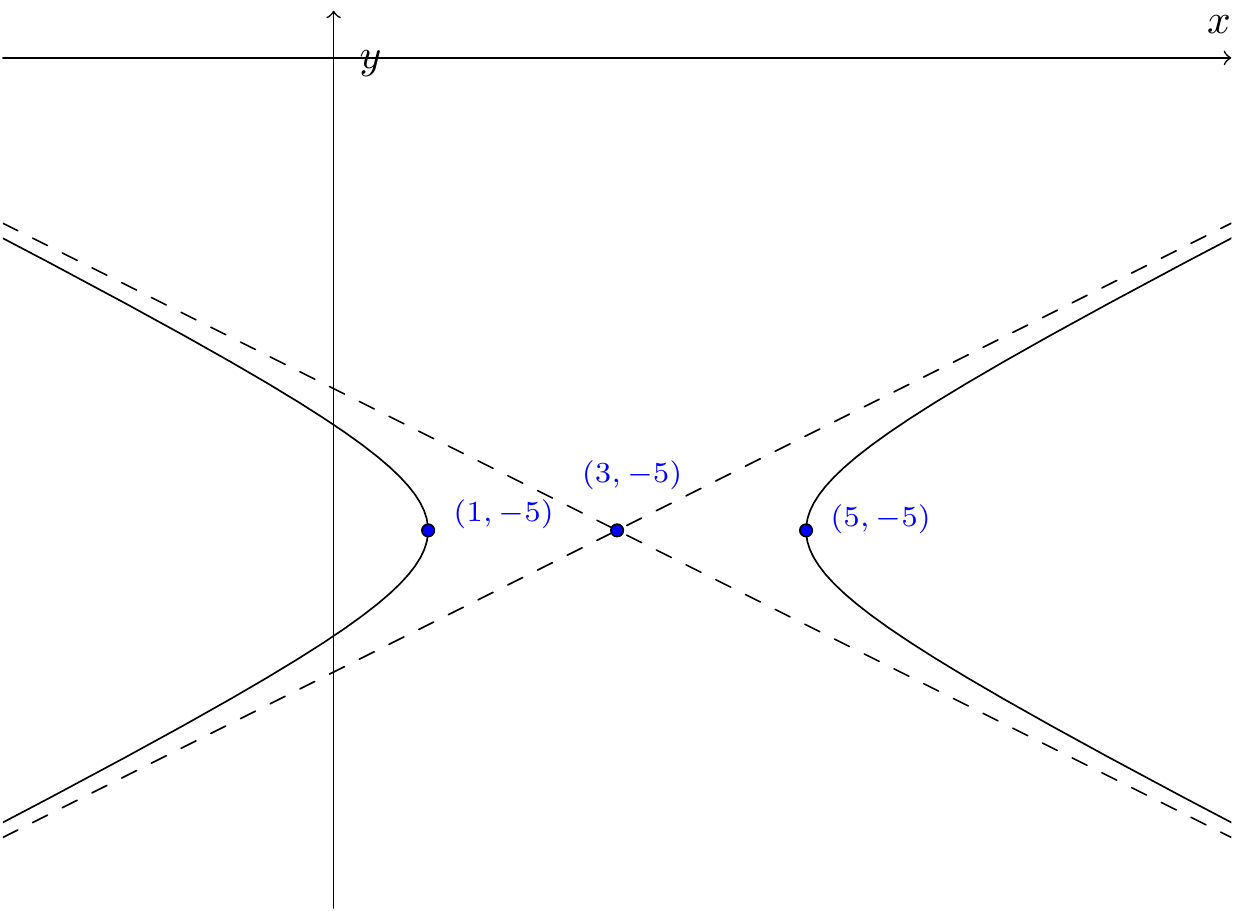

- We do the same again: \((x^2-6x)-4(y^2+10y)-95=0\), and then \[(x-3)^2-9-4(y+5)^2+100-95=0.\] This rearranges to \((x-3)^2-4(y+5)^2=4\), or, dividing by \(4\), we get \[\frac{(x-3)^2}{4}-(y+5)^2=1,\] and we recognise this as a shifted hyperbola with centre \((3,-5)\).

Figure 7.41: The second example: a hyperbola

Note that general quadratic could represent ‘nothing’, e.g., \[(x-2)^2+(y-3)^2+8=0,\] which has no solutions (the left-hand side is always positive). It can also represent two parallel lines, e.g., if we have \(x^2-2x=0\) (so all the other coefficients vanish), then \(x(x-2)=0\), and we get two lines \(x=0\) and \(x=2\). We could just get one line, for example, \(x^2-2x+1=0\) becomes \((x-1)^2=0\)

The case \(B\ne0\) involves rotating the coordinate system in such a way that in the new system \((x',y')\) there is no \(x'y'\) term.